By Lian Cheng

“They (politicians in Kuala Lumpur) were waiting for Abang Johari, waiting for GPS where the nation was in chaos and we wanted to make it peaceful again.” Abang Johari (March 4, 2020)

THE 14th General Election, held on May 9, 2018, marked a transformative chapter in Malaysia’s democratic journey. The outcome of this unforgettable election was a historic turning point that reshaped the nation’s trajectory, ushering in a new era in Malaysia’s governance. In an unprecedented turn of events, for the first time since its independence, the 13-member Barisan Nasional (BN) ruling coalition led by the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) collapsed, as the opposition coalition Pakatan Harapan (PH) formed the new federal government. PH, comprising a pact between Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR), Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia (Bersatu), Democratic Action Party (DAP), and Parti Amanah Negara (Amanah), secured a simple majority with 113 seats, while BN polled 78 seats and Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS) obtained 30.

In the eleventh hour of that whirlwind day filled with political upheaval, BN lost its hold on nearly all states in Peninsular Malaysia, retaining only two. Its stronghold in East Malaysia also stood on shaky ground, with Sabah choosing to align itself with PH, while Sarawak was faced with the weighty decision of which side to support—a choice that would ultimately tip the balance and determine the direction of Malaysia’s administration. Following PH taking over Putrajaya, the coalition agreed for Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad, former Prime Minister and leader of Bersatu, to return as Prime Minister. This decision was made in light of Dr Mahathir’s considerable influence, serving as a strategic move to unite the opposition against the long-ruling BN coalition. The agreement also stipulated that Dr Mahathir would step down after two years to make way for PKR president Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim to assume the role.

PH’s victory in securing 113 out of 222 parliamentary seats resulted in a fragile government, one that remained vulnerable to collapse. This gave rise to rampant horse-trading and intense political manoeuvring. Eventually, Warisan—a party from Sabah that had won eight seats—joined the ruling coalition, raising PH’s total to 121 seats.

The Formation of GPS, the Third Force

Meanwhile, like the rest of BN counterparts, Sarawak BN, which consisted of Parti Pesaka Bumiputera Bersatu (PBB), Sarawak United Peoples’ Party (SUPP), Parti Rakyat Sarawak (PRS), and Progressive Democratic Party (PDP), found itself in uncharted territory, confronted by a situation unlike any it had encountered before. Despite being allocated 31 out of the 222 parliamentary seats, Sarawak BN had been subordinated to UMNO, even while being regarded as a fixed deposit for the coalition. However, with PH securing a narrow victory and the political landscape being volatile amid threats of party-hopping that could easily tilt the balance, Sarawak BN, having retained 19 of its 31 seats, emerged as the kingmaker. Its support was highly sought after, particularly as all its elected parliamentarians were viewed as steadfast and loyal, untouched by the game of political backroom wheeling and dealing.

At that juncture, Sarawak BN stood at a crossroads: either join PH to reinforce the new ruling coalition or remain with BN in opposition. Abang Johari, however, chose a different course, with Sarawak aligning with neither. In a game-changing move, he announced Sarawak’s withdrawal from BN while simultaneously declining to join PH. Together with leaders of the component parties, he took a bold stand, navigating waves of uncertainty as they resolved to form a new local ruling coalition: the Gabungan Parti Sarawak (GPS). As the political scene in Putrajaya remained volatile, Sarawak’s decision triggered intensified overtures from both BN and PH. Yet, GPS stood its ground, maintaining its stance as an independent third force in Malaysia’s high-stakes political arena but a friendly one to the Federal government.

The Sheraton Move

On February 23, 2020, almost two years into PH’s administration, Malaysia was once again plunged into political disarray as long-simmering tensions between major parties finally came to a head. Several key factions from both PH and BN began convening for a series of ‘secret’ meetings at various locations. The most significant of these took place at the Sheraton Hotel in Petaling Jaya. Infamously dubbed the ‘Sheraton Move’, in reference to its venue, this gathering triggered a chain reaction of political upheavals that ultimately led to the formation of a new federal government under Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin, the president of Bersatu.

By the time news of the ‘Sheraton Move’ broke in the press, speculation was rife that a new ruling coalition was being formed to replace PH, excluding the DAP and the faction of PKR led by its president. Amid the rumours, a series of behind-the-scenes agreements and shifts in allegiance had already begun to unfold. On the following day, February 24, the faction of PKR aligned with Anwar, together with DAP and Amanah, met with Dr Mahathir to seek clarification over the unfolding events. Anwar denied involvement in the ‘Sheraton Move’. Meanwhile, a splinter faction of PKR led by Datuk Seri Mohamed Azmin Ali was expelled from the party and subsequently formed an independent bloc.

Amid chaos, Dr Mahathir announced his resignation as prime minister and chairman of Bersatu, triggering the automatic dissolution of the Parliament. He was, however, appointed by the King as the interim prime minister. At the same time, Muhyiddin declared Bersatu’s withdrawal from PH. With its exit and Azmin’s faction leaving PKR, PH lost its parliamentary majority, and with it, its control of the government.

Muhyiddin, the Eighth Prime Minister

Between February 25 and 26, the King conducted interviews with 221 Members of Parliament (MPs), excluding Dr Mahathir, to ascertain their support for the two prime ministerial candidates—Dr Mahathir or Anwar. Following the interviews, it was revealed that 90 MPs supported Anwar, while 131 backed Dr Mahathir, including 19 GPS MPs from Sarawak. The outcome, however, was not convincing enough for the King to make a final decision. On February 27, quoting the King, Dr Mahathir announced at a press conference that no clear majority had emerged for the appointment of a prime minister, and a special session of Parliament would be held on March 2 to resolve the impasse. He did not rule out the possibility of a snap election. On February 28, after a special Conference of Rulers meeting, the King convened party leaders in an effort to reach a decisive solution to the political deadlock. Later that day, another unexpected turn occurred. A total of 26 Bersatu MPs, 11 MPs aligned with Azmin, 60 UMNO MPs, along with MPs from PAS, Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA) and Malaysian Indian Congress (MIC), publicly expressed their support for Muhyiddin to be appointed as the next prime minister. The following day on February 29, GPS issued a statement pledging its support to the emerging ruling coalition—Perikatan Nasional (PN), as a friendly party, not as a member. With politicians in Peninsular Malaysia divided into two distinct camps, the 19 GPS MPs, who emerged as a strong united pack became the kingmaker. On March 1, 2020, with the backing of GPS, Muhyiddin was sworn in as the Eighth Prime Minister of Malaysia. Nine days later, he announced the new cabinet and formed the PN government.

The PH administration collapsed after only 22 months in power. GPS, holding 19 parliamentary seats, agreed to support Muhyiddin for the sake of national political stability. A GPS press statement explained the decision. According to their press statement, “only by being stable can the federal government deliver and implement socioeconomic development to the country, including to Sarawak.” It came amid rumours of an impending no-confidence motion against Muhyiddin, as Parliament was scheduled to convene on March 18. At this stage, the struggle for political control had shifted from a rivalry between Dr Mahathir and Anwar to a contest between Dr Mahathir and Muhyiddin. This abrupt change triggered a fresh wave of political manoeuvring and “party-hopping”, with several MPs switching allegiances.

Meanwhile, on another front, Malaysia had confirmed its first Covid-19 case on January 25. By then, a local cluster linked to a Tablighi Jamaat religious gathering in Sri Petaling, Kuala Lumpur, had emerged. As Prime Minister, Muhyiddin implemented a three-month Movement Control Order (MCO) beginning March 18 to contain the spread of the virus. The pandemic, in effect, slowed down political machinations and provided Muhyiddin with crucial time to consolidate his position in Putrajaya. On May 18, Parliament convened with only the King’s royal address marking the opening of the new session. By then, political tensions had largely subsided, and national focus had shifted decisively to fighting and curbing Covid-19. As Malaysia turned its full attention to combating the pandemic, Muhyiddin’s position, whether viewed as a backdoor government or otherwise, appeared to be secure.

During both major political upheavals—the first which resulted in Dr Mahathir’s return as Prime Minister, and later, the power struggle which led to Muhyiddin’s appointment as the Eighth Prime Minister—Sarawak’s GPS, with its consistent bloc of 19 parliamentary seats, played a pivotal role in the formation of both governments.

Ismail Sabri, the Ninth Prime Minister

Malaysia’s political landscape remained volatile even after Muhyiddin assumed the role of Prime Minister. The PN government, built on fragile alliances and often dubbed “backdoor government”, was plagued by ongoing internal friction, largely driven by leaders within UMNO who repeatedly threatened to withdraw their support, jeopardising the survival of the PN administration. Even within UMNO, the largest bloc in the ruling coalition, internal division persisted. One faction was led by UMNO president, Datuk Seri Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, while another aligned with UMNO MP, Datuk Seri Ismail Sabri Yaakob. Muhyiddin’s claim to a parliamentary majority was also disputed. The eventual withdrawal of support from Zahid’s faction provided PH with the political leverage it needed. Capitalising on the moment, PH pushed for a vote of confidence in Parliament. With his majority no longer assured, Muhyiddin announced his resignation on August 16, 2021.

Four days later, on August 20, 2021, Malaysia saw the return of its former ruling party to federal leadership as Ismail Sabri was appointed the Ninth Prime Minister by the King. To consolidate power and prevent further instability, Ismail Sabri signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with PH, marking a rare instance of bipartisan cooperation. However, the period of calm proved to be short-lived. Political instability in state legislative assemblies led to unavoidable elections in Melaka and Johor. The situation was further complicated by persistent internal pressure. Left with few alternatives, Ismail Sabri announced the dissolution of parliament on October 10, 2022, triggering a snap general election in November that same year.

A Hung Parliament

As predicted by many, the 2022 General Election held on November 19, failed to resolve Malaysia’s ongoing political turmoil. Instead, it resulted in a hung parliament, with PH secured 82 seats, PN 74, BN 30, and GPS won 23 of the 31 seats its contested. Even during the campaign period from November 5 to 18, GPS was consistently regarded as the kingmaker, owing to Sarawak’s political stability and Abang Johari’s popular inclusive policies, which had fostered unity among Sarawakians. Political analysts and observers broadly agreed that whichever coalition—PH, BN, or PN—sought to form a government would require GPS’s support to establish a convincing parliamentary majority. As anticipated, with the backing of BN, GPS and Gabungan Rakyat Sabah (GRS), PH succeeded in forming the federal government. On November 24, 2022, Anwar was appointed Prime Minister to lead the new coalition administration.

The years between 2018 and 2022 marked a chaotic and tumultuous chapter in Malaysia’s political history. Within just four years, the country witnessed the collapse of three successive coalition governments—PH, PN, and BN—and the appointment of three prime ministers, all amid the far-reaching impacts of a global pandemic.

Sarawak, the Biggest Winner

Amid waves of political uncertainty, GPS’ support proved critical to all three ruling coalitions that assumed control of Putrajaya at different times. Throughout this period of shifting governments and political turbulence, GPS consistently maintained that its decisions were guided by the broader goal of ensuring national political stability, rather than narrow self-interest.

Under Abang Johari’s leadership, Sarawak emphasised the importance of long-term steadiness over short-term political advantage. As a result, Sarawak, through GPS, emerged as a vital stabilising force in Malaysia’s political landscape.

Abang Johari’s approach centred on maintaining composure amid national uncertainties, positioning Sarawak as a key player in supporting governmental continuity. His commitment to fostering unity and accommodating diverse interests ensured that Sarawak’s influence remained central to the stability of the Malaysian government. On the home front, Abang Johari successfully insulated Sarawakians from the turbulence unfolding at the national level, keeping their attention focused on development and the well-being of the State and its people.

He introduced a series of transformative initiatives to drive Sarawak’s growth across various sectors, ensuring the State’s progress continued uninterrupted despite the surrounding volatility. Under his leadership, Sarawak stood out as a model of stability and progress during a period marked by widespread political upheaval.

GPS, the Kingmaker

On May 14, 2023, Anwar reaffirmed his view of GPS’s role as kingmaker during the hung Parliament following the 2022 General Election. He recalled the “moment of truth” when, despite PH having won the most seats, still fell short of achieving a simple majority.

“From the Yang di-Pertuan Agong’s (point of view) during the critical situation, Premier Abang Johari and GPS were the determining factor (kingmaker),” he said.

Sarawak’s political stability, and the resulting economic momentum, soon became a source of envy. Accusations surfaced, alleging that the State’s success was rooted in opportunistic exploitation of Peninsular Malaysia’s shifting political dynamics. Abang Johari dismissed such claims as part of a “jealousy narrative”. He called on critics to look past the smoke and mirrors, urging them to understand that Sarawak’s achievements stemmed from sound economic policies and an unwavering commitment to stability.

Speaking during a townhall session marking his eighth anniversary as Premier at the Hikmah Exchange and Event Centre (HEEC) on January 13, 2025, he refuted the suggestion that Sarawak’s progress was the by-product of federal political turmoil. Instead, he emphasised Sarawak’s consistent support for Malaysia’s national leadership, be it under Dr Mahathir, Muhyiddin and Ismail Sabri. That support, he said, was not driven by opportunism but by a fundamental belief that political stability is the bedrock of economic development.

Sarawak’s decision to back the current PH-led government, he explained, was rooted in the same conviction: that national progress, especially in the face of global economic headwinds and climate challenges, can only be achieved through sustained political stability. Sarawak also backed the current government under PH for the very same reason—its conviction that political stability is essential to ensuring the nation’s progress and development, and to address more pressing external challenges such as climate change and global economic uncertainties.

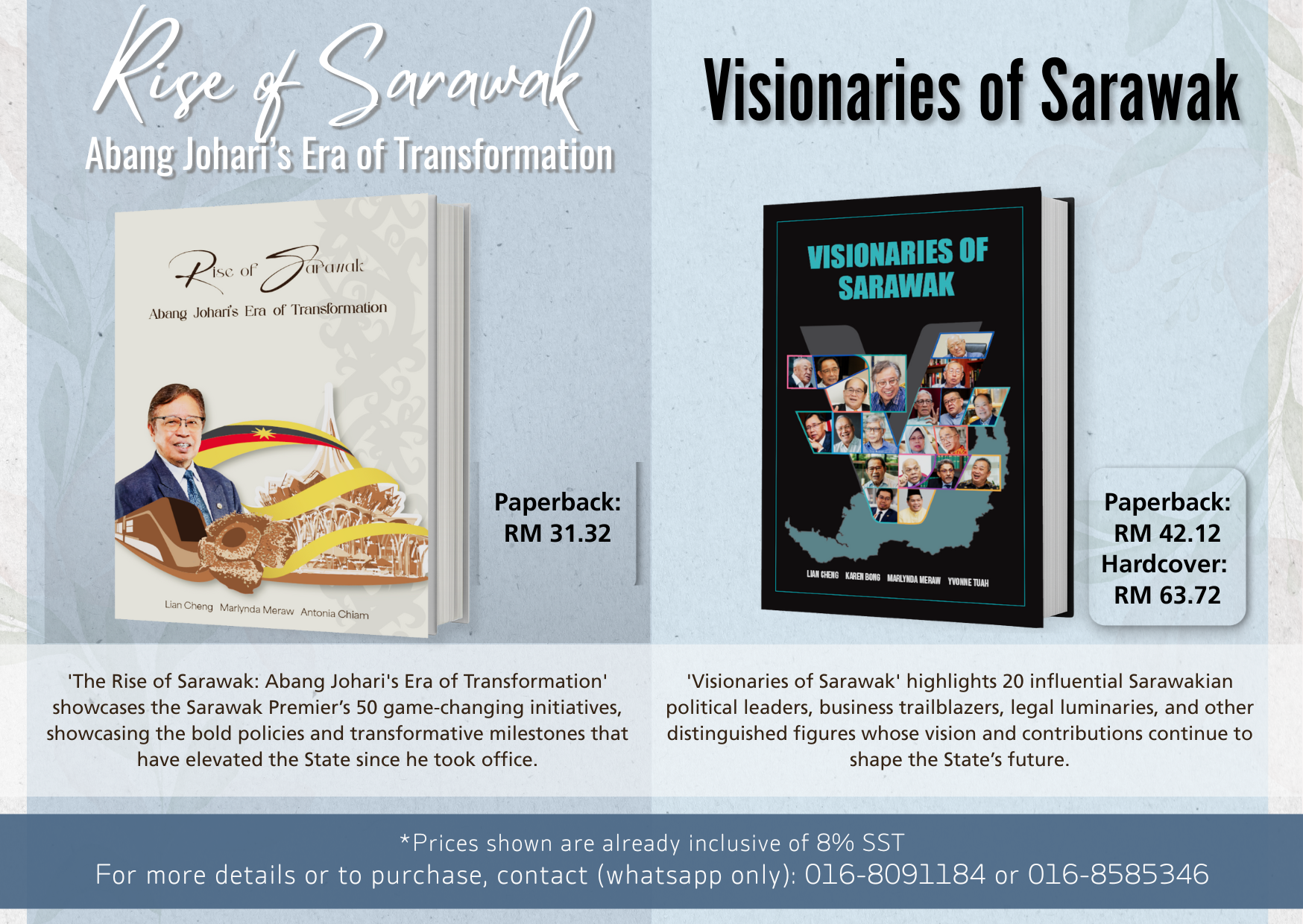

The content featured here is an excerpt from the book “Rise of Sarawak: Abang Johari’s Era of Transformation”, published by Sage Salute Sdn Bhd. All information contained herein is accurate as of the first quarter of 2025.